Story courtesy of The Salem Magazine, Will Broaddus.

Sailing is a science as well as a sport. Robbie Doyle, a longtime resident of Marblehead who grew up in Salem, Massachusetts has been proving that point throughout his career, both in the business world and on the water.

That fact was acknowledged when Doyle was recently inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame and his “high-tech approach to sail making” was cited.

“It’s totally a science now,” Doyle says. “It was totally an art when I got involved. That’s been the transition it’s gone through,”

Doyle, 70, started sailing when he was 7 years old, because his brother had fallen out of a crib and broken some vertebrae. “It all healed, he was fine, but the doctor suggested to my father he does not play contact sports,” Doyle says.

So when Doyle’s brother turned 6, his father enrolled the whole family in a sailing program at the Medford Boat Club. “We had six children in our family, and you didn’t sign one person up for one thing,” Doyle says. “The whole tribe would go and get dropped off.”

Doyle says the lessons he received in Medford were unique, in that the older children taught younger ones how to sail. “I think out of that group that I was at, that school sailing program, say when I was in sixth or seventh grade, I think about eight of them became college All-Americans at one time,” Doyle says.

After his father bought a summer home in Marblehead, the children were also signed up for the Pleon Yacht Club, a junior yacht club on Marblehead Neck, and sailed there all summer.

Doyle was good enough at sailing to win “a couple of North American Junior Championships, although he was still more interested in baseball, basketball, football, and swimming.

But he also desperately wanted to compete in the Olympics and knew he wouldn’t make the team in any other sport, “Sailing just seemed to come easy, and then I had a shot at it, and went to the Olympic trials in ’68 and qualified,” he says. That was during the summer of his freshman year at Harvard, where he was on the sailing team and studied engineering.

“I started in social relations, believe it or not, and then I guess it turned out I was too much of a scientist,” Doyle says.

Many of the courses in Applied Physics that he wanted to take weren’t available at Harvard, but the school allowed Doyle to study instead at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he took courses from a man named Jerry Milgram.

“One of the things I took was Fluid Dynamics, which is the flow of fluids, which is air, water, anything,” Doyle says.

Fluid Dynamics can be used to analyze anything that behaved like a fluid, such as traffic patterns, where the motion of cars is measured in the same way as molecules.

“Everything flows,” Doyle says. “So I ended up in fluid dynamics. I also at one point was really interested in – and probably still am – in oceanography, the flow of ocean currents.”

When he applied fluid dynamics to sailboats, Doyle saw that the way they flow through water is determined by two conflicting forces: wind on the sails and water against the keel.

“You had a deflector of wind, and it would push the boat sideways,” he says. “The keel wouldn’t let it go sideways, so it would go forward.”

This formula led to innovation when Doyle used it to figure out how the precise shape of a sail, and the material it is made from, determined how well it harnesses the wind. “People at first “didn’t really understand or fully believe that you would look at a sail as close as the wing of an airplane”, he says, where the lift is affected by areas of low and high pressure.

“That would have been 50 years ago, and some people didn’t believe there was any aerodynamics in sails,” Doyle says.

Putting the Science in Sails

The career in which Doyle proved his formula was true began at Hood Sails in Marblehead in 1972. The shop was run by legendary yachtsman Ted Hood, whom Doyle had met several years before at an awards dinner.

“At some point, he and his right-hand man came up and said, ‘Robbie, you’ve got to come by and work for us,’” Doyle recalls.

Once Doyle came on board, Hood wanted him to develop a new Genoa, a type of sail, that is used at the front of a boat when the wind is light.

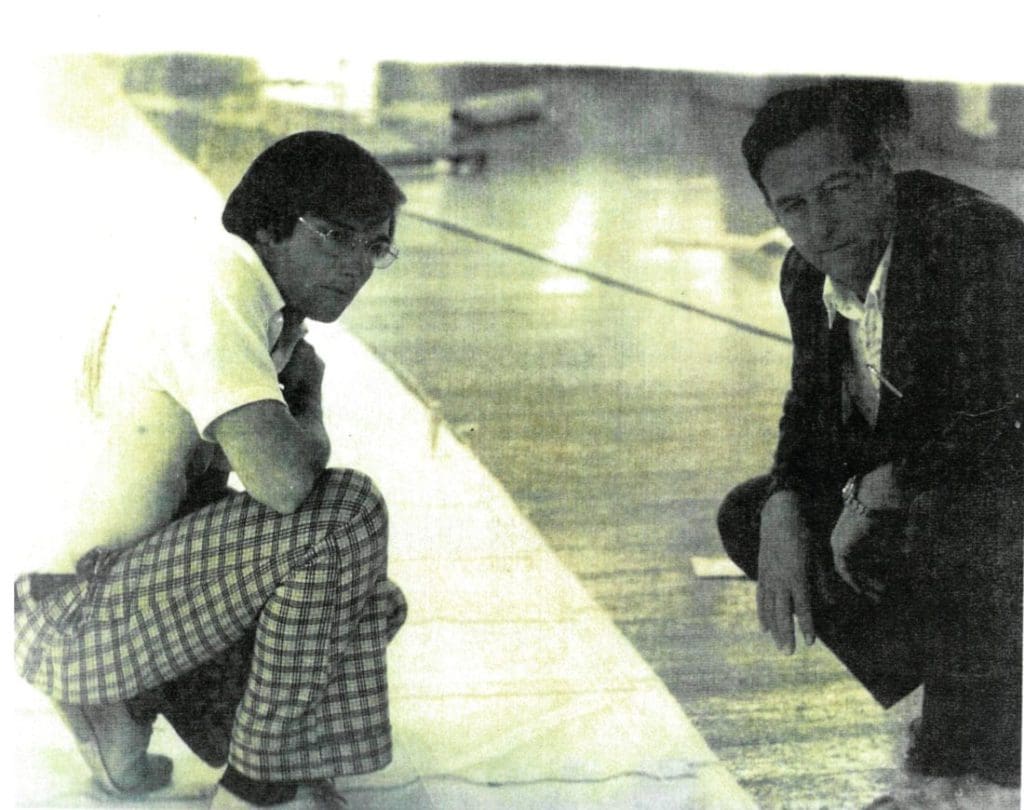

Robbie Doyle and Ted Hood at Hood Sailmakers in 1976

As Doyle explains it, a boat can use as many as 20 different kinds of sails, depending on whether it is sailing with or against the wind, in the same way, that a bicycle has 20 gears that help it to go uphill or downhill.

“So I came in and took a look at how Hood was doing things,” he says. “I had some theories about how I thought it could go better and started designing sails a little bit more scientifically than Hood had been doing in the past.”

That was in the summer of ’72 when Doyle thought he would be going to medical school in the fall to become a doctor like his father. But he decided to put it off for a year so he could help Hood race in the Canada’s Cup, which was held during September and October.

“It’s a mini America’s Cup type thing, and so I was able to get a little bit involved in the boat design, and I sailed on the boat,” Doyle says. “It was just a lot of fun. I was like a kid in a candy store.”

Doyle never did become a doctor, as he continued to design sails for Hood’s company and also created sails for Ted Turner’s entry in the 1974 America’s Cup, Mariner.

“It was probably the world slowest 12-meter ever,” he says of the boat. “It was an experimental thing that just didn’t work.” But the sails themselves worked fine, and Hood used them instead of another set on Courageous, which he skippered that same year.

“Mine was a little more tailored to our 12-meter,” Doyle says. It turned out to be a successful America’s Cup, and at this point, it was not long after that Ted asked me to become General Manager of Hood.”

Although Hood would eventually offer to sell the company to Doyle, he didn’t accept and finally left in 1983 – fittingly enough, on Independence Day – after a new owner took over.

“I had no plan to go start my own sail-making company,” he says. “Everybody says I did, and everybody says Turner backed me. I really had no plans. I figured I’d take some time and think about it and the right thing would happen.”

But his wife had just delivered their third child, and they had also purchased a house, so it wasn’t too long before Doyle announced that he was starting a company to make sails.

“Completely surprising, if not shocking to me, one key person after another from Hood walked in the door and said, ‘Robbie, things aren’t the same, I’d like to join you,’” Doyle says.

Supersize Growth

Doyle Sails was on Front Street in Marblehead for around 25 years and grew with each new order that the business landed.

“One after another, we began to get some big clients, and the initial sails we did all performed extremely well, so that just led one thing to another,” he says.

In the same way that a workforce had flocked to Doyle’s door, sail lofts from around the world started asking to join his company in a licensing program.

“We grew to about 70 or 80 lofts within seven or eight years, from 1984 to 1990,” he says.

Although Doyle Sails offers a range of services, the company made its mark creating sails for Superyachts like the 300-foot Maltese Falcon, which was built by a venture capitalist named Tom Perkins.

Tom Perkins sought out Robbie Doyle to build the sails for 2nd yacht the 88-metre, three-masted ‘Maltese Falcon’

Doyle says the world of sailmaking right now is dominated by the brand that bears his name and one other, North.

“They were bought out by a billionaire, who invested a lot of capital,” Doyle says.

“We were growing faster than they were at the time, but when a billionaire comes in and can put real capital in – they’re bigger than we are, and we’re probably No. 2, image-wise we’re No. 2.”

There are currently 40 employees working in the 32,000 square foot Doyle Sails loft on Swampscott Road in Salem, where the operation moved in 2007.

Craftsmen use sewing machines that cost more than Doyle’s first house to make sails out of materials that have evolved from synthetics such as Dacron to carbon fiber, which feels like a dense feather.

There are also two sails designers, Travis Meindl and James Moody, who use 3D programs to visualize sails performance from every possible angle, while highlighting wind stresses on each sail’s surface, with a range of colors.

While the formulas of fluid dynamics still define how boats and sails are designed, computers now do all the math.

“To design the next America’s Cup boat, the American syndicate that’s running it, the first thing they did was hire 31 computational fluid dynamic people to design the boat,” Doyle says.

“These computers predict exactly how fast the boat will go in each wind speed, how the boat will perform, and then the engineers have to design the materials to withstand the forces, and they don’t want 1 gram extra.

That’s one of the several reasons why the American program for the next America’s Cup has a budget of around $120 million, Doyle says, and relies on sponsorship from a range of automakers and software companies.

Doyle recently sold his own company to his New Zealand license and is semi-retired, but still manages special projects from the loft in Salem.

Robbie Doyle and Mike Sanderson at the 2017 America’s Cup – signifying the brand hand over.

He also works as a professional sailor about 100 days out of the year, on other people’s yachts all over the world.

But Doyle’s own boats are a far more modest 33-foot powerboat and a 15-foot wooden day sailor in the Town class, a “Townie,” which is a type of boat that originated in Amesbury in the 1930s.

As a professional, Doyle isn’t allowed to race the Townie in local competitions, which are strictly for amateurs, but that’s fine with him.

“I bought it to go sailing with my grandchildren,” he says. “Actually, my daughter goes sailing. It’s a centerboard boat, you can pull it up on the beach. It goes back to how we learned to sail.”

Story courtesy of The Salem Magazine, Will Broaddus.