Unlike with colleague Jud Smith, there is indeed more than one ‘Robbie’* in the sailing world, but there’s only one who gave his name to a now iconic yellow sailmaking logo. And so I can’t call him ‘Doyle’, says Carol Cronin, or you’ll think I’m talking about the global company instead of a New Englander now more focused on golf than sailing

From Seahorse Magazine // March 2025

Writing for Seahorse rarely brings fringe benefits but when I nail down an interview with Robbie Doyle he invites me to share a meal with him and his wife and former business partner Janet. Their Marblehead home is cosy and lived-in, so I ask how long they’ve been there. The answer – 40 years – begets another question: where are they hiding all the trophies?

I’m not expecting to see the America’s Cup (which he won twice), but there have been plenty of other significant victories over the past 60 years… Robbie just shrugs. ‘We don’t even know. Some people have trophy rooms… but!’

‘He’s never been one to look back- wards,’ Janet says. Nodding, Robbie con- firms: ‘I’m afraid that I was always looking forwards.’

And that is the first of many insightful comments from Janet, who both fact checks and edifies their rich history. While simultaneously preparing and serving up an excellent lunch.

Childhood freedom

Robbie Doyle grew up a few towns inland from Marblehead, and his first sailing took place on a tiny, hill-shrouded lake. Once his parents bought a summer house near the coast he and his brother would sail their Turnabout prams out of Salem Harbor and ‘around the corner’ to Marblehead. ‘We’re seven years old, and we’d sail out of sight – no lifejackets, obvi- ously.’ Robbie shakes his head.

Once they reached Pleon Yacht Club, the independent juniors-only wing of the Eastern Yacht Club, ‘we’d just hang around and go sailing, or sometimes race on weekends. And then we’d sail back. We just had free rein,’ he says, adding that if a squall came through, ‘we’d tie up to a lobster pot and hide under the sail. And no one came out and got us!’

Robbie was the fifth of six kids, Janet explains. ‘By the time [his parents] got to their last two they were older and they were tired. Discipline was pretty much gone.’

I ask where they met, and that also takes us back to Pleon. ‘We were 13 and 14. And we’ve been married coming up on 52 years,’ Janet says proudly, before adding a perhaps even more impressive statistic: ‘And we worked together for 30 of those years.’ Janet became the ‘people manager’ at Doyle Sails in 1990 and retired in 2020. ‘If anyone had an issue they called Janet,’ Robbie tells me later.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, so I ask what came after the Pleon years. As a teenager Robbie had only a vague career idea of following his father into medicine. But he already had one very concrete life goal: to go to the Olympics.

In high school he ran track, played tennis and also set several regional records in swimming. (‘I’ve never met a sport that didn’t love Robbie,’ says Janet.) Basketball was his favourite, but ‘I was never going to go to that level; a short white man who can’t jump.’

He entered Harvard with ‘no idea what I was going to do’, while Janet went off to sec- retarial school. ‘But I spent most of my time on the train, going to see the boyfriend,’ she admits. ‘I typed all of his papers; you know, the pathetic thoughts back in those days: when he looks good, I look good.’

At university Robbie says, ‘Sailing just came easy; it made sense.’ So he started training for the 1968 US Finn Trials, which would be on the west coast the summer after his freshman year.

Olympic alternate

Best friend Carl van Duyne became his training partner. ‘I beat him so badly here that he decided he wasn’t even going to the Trials… but I talked him into it!!’

The east coasters were ‘clearly the two fastest boats’, Robbie says. ‘I led up until the second to last race, when my mainsheet block pulled out. That was going to be my throwout…’ until Carl match-raced him back in the last race, a heated battle that involved ‘calling mast abeam more than a few times…’ Robbie finished second. More than half a century later he can still describe that final race blow by blow.

Perhaps sensing his unique combination of versatility and drive, the US Olympic team selected the 19-year-old as their sole alternate. He flew to San Diego to help Lowell North in the Star and also helped the Flying Dutchman team. ‘I actually sailed the Finn and Star practice races!’

Robbie had to take a leave of absence from Harvard to go to the Games, and his country expressed its gratitude by serving him with a draft notice. ‘I was not a big believer in the [Vietnam] war,’ he explains, still grumpy that ‘Even though you’re quote representing your country, that didn’t count’ toward an exemption. ‘Which is stupid… The Harvard rowing team was in the Olympics that year too; they all took the whole year off. And they didn’t get drafted.’

Luckily there was a college exemption and so ‘now it became a scramble’ to get back into Harvard for the spring semester.

Back to school

By the time he returned to university Robbie had decided to study engineering. Harvard’s closest major was applied physics, ‘and I really wasn’t a physicist’.

When Robbie asked his adviser what he should do the response was ‘do you know anybody at MIT?’ The two schools had reciprocity – and Robbie had recently met Jerry Milgram. He soon found himself engrossed in the quite new field of compu- tational fluid dynamics (CFD).

Their most memorable experiment used the towing tank to test a sail for the Inter- club dinghy, the local frostbite class. Although their data was skewed because the cloth’s melamine resins were water soluble, ‘we still came up with some good ideas, so I decided to build myself a sail. And we won every race that next Sunday!’

But soon after sailing the fast design mysteriously disappeared. ‘Basically we’re convinced someone stole it… but it never saw the light of day again.’

Jerry was a fascinating guy, Robbie adds. But in the early 1970s ‘no one had the computer power to find out whether ideas were right or wrong. You had to use coefficients; test the theory against an actual result, and then scale up or down.’ Scaling creates inaccuracies, he continues, because ‘Reynolds numbers don’t stay the same, vortices don’t shed the same way, energy is lost in different ways. So even simulating trimming sails is difficult.’

A generation later Robbie would introduce his son to Jerry. ‘Tyler ended up going to Stanford and working on a PhD there in computational fluid dynamics,’ the proud father explains.

‘So Jerry says, “What do you want to do with CFD?” And Tyler tells him, “Well, I think I’ll work on it as a career.” And Jerry says, “There’s no money in it. I wouldn’t even think of doing that.” Tyler’s spent his whole life studying this stuff! But Jerry could be a little cranky, so we weren’t surprised or put off.’

Harvard or Hood… or both

There was a saying on the Marblehead waterfront in the 1970s that if you didn’t go to Harvard you went to work at Hood Sailmakers; Robbie did both.

He first met Ted Hood at an awards ceremony in the autumn of 1971, and the affable owner suggested Robbie stop by when he finished school. ‘I got out on 2 February [1972],’ Robbie says now. ‘3 February I showed up in his office and said, “You asked me to come by!”’ Ted asked if Robbie could design sails, Robbie said yes, and ‘he says, “Fine, you’re hired.” So that’s how I started at Hood.’

It was exciting to join the legendary company, but Robbie assumed it would be just a temporary money-making filler until he started medical school in the autumn. Instead, ‘I basically created [Hood’s] design department.’

And it wasn’t just sails. ‘Soon Ted and I were wandering downstairs to the design office after work, “to see what they were looking at: What do you think about this? What about that?”’

After sailing Solings with Dave Curtis, Robbie says that ‘sailing big boats drove me crazy because you couldn’t adjust the backstay’. Even those big turnbuckle wheels couldn’t be turned fast enough. So one afternoon he suggested that Ted add a block and tackle to the new Two Tonner Dynamite that Ted had designed for the Canada’s Cup.

When another member of the Hood brain trust jokingly proposed a hydraulic ram, ‘Ted looked at both of us and said, “Why not?”’

Their first prototype quickly rusted solid so they made a better one out of stainless steel. ‘And that’s how we started the whole hydraulic backstay thing,’ Robbie says. He also ‘designed the sails, helped build them and became a trimmer’ on Dynamite. ‘And we won the Canada’s Cup.’

That success led to many other collabo- rations – including applying hydraulics to a mast ram that helped Flyer win the Whiltbread Round the World Race. ‘There was never an idea Ted was afraid of trying: build it, break it, fix it. It was really a lot of fun working with him.’ To this day Robbie values the opportunity to ‘walk next door and say, hey, what the heck is this? That just accelerates everything.’

To compete in the Canada’s Cup Robbie had been granted a year’s deferral from medical school. The following year, when he asked for another delay, they said he’d have to reapply. And with the 1974 America’s Cup on the horizon his ‘tempo- rary’ career as sailmaker had an obvious path forwards. So did his personal life: Robbie and Janet married in 1973.

The less obvious question: which Cup team?

First Cup

Long before Ted Hood replaced Coura- geous’s original skipper Bob Bavier for the 1974 summer, that syndicate invited Robbie for a try-out. But another Ted (Turner), a fellow Finn sailor, offered up an actual position: sail designer and co- tactician with Dennis Conner, onboard Mariner. ‘So I turned down an invite fromCourageous to sail on Mariner. It was a long, long summer…’

He (and everyone else) soon realised that their boat was slow. ‘If you want to be a good tactician you get a fast boat. So I told Dennis, “Let me concentrate on the sails and sail trim. You can work on the tactics.” And he goes, “Yeah, thanks a lot, Rob.”’ He chuckles at the memory.

Once Mariner was eliminated Conner joined the Courageous afterguard – with Ted Hood also called on to help with the sail programme. Courageous had two full sail inventories (Hood and North). ‘Ted didn’t like the North main; he sincerely didn’t agree with what they were doing. And the Courageous sails were rough; no one was really attending to them. So Ted said, “Robbie, you’re going to come over and work with us.”’ His boss actually wanted him to trim main, but they already had a good trimmer. ‘So I said [again], “Let me just focus on the sails.” We brought Mariner’s main over, and we built a bunch of new sails that all worked out well. Sail- ing during the day, building sails at night – that was a fun, interesting campaign.’

When Courageous swept Southern Cross 4-0 it displayed (as the America’s Cup website now puts it) ‘the sheer might of American sailing… Four syndicates, a long summer of optimisation and crew changes that finally produced a standout contender.’ (Ah, those were the days!).

Robbie had made the right career choice. Though he probably would have become an equally outstanding doctor.

Cup #2

‘My first phonecall when the series was over was to Ted Turner,’ Robbie tells me now. When he suggested the southerner somehow get his hands on Courageous, the Atlanta Hawks owner invited him down to watch a pro basketball game. After that Ted said that he would skipper Courageous as trial-horse for Ted Hood’s new Independence. That seemed like a good deal for everybody…

Except that the trial-horse outsailed both Independence (restricted to Hood sails) and Lowell North’s new S&S design Enterprise (restricted to North sails), win- ning 11 of 12 races to decide who would represent the New York YC in the Match.

At the end of that 1977 summer, with Turner as skipper, Gary Jobson as tacti- cian and flying an unhindered combina- tion of North and Hood sails, Courageousagain swept the America’s Cup – this time with Robbie Doyle trimming main.

Robbie and Janet had Tyler, the first of their three kids, in the spring of 1977. By 1980 they had a one-year-old and a three- year-old – and Ted Turner’s Courageous lost to Dennis Conner’s Freedom. With Tom Whidden calling tactics, Freedom would certainly not be switching over to Hood products to defend the Auld Mug. The family headed back to Marblehead.

Independence Day

Hood Sailmakers was sold in 1982, and on 4 July Robbie hung up the very first Doyle Sailmakers sign. Their tagline was ‘Better Engineered Sails’, embracing the brave new world of computerised sail design. In 2010 he told another magazine that ‘he didn’t open a sail loft in Marblehead because the area needed another sail- maker… he thought he could make better sails than any of them.’

‘Tiny little spot,’ he says now, but ‘we did a lot in 6,000ft2.’

Robbie skipped (losing) the 1983 Cup to focus on his quickly growing business. By 1990 there were 70-80 lofts showing off the yellow Doyle logo around the world – and many more happy clients.

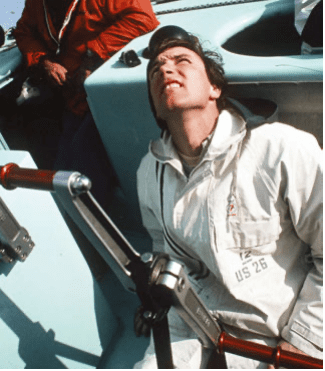

Even with crew below to reduce aero drag, Dennis Conner on the wheel (above) and Ted Turner there as tactician Mariner could not get out of her own way, her truncated bustle dragging a large chunk of ocean behind her on every point of sail. She had lovely Hood sails, though (right) – which along with DC would later make their way across to Courageous for a successful America’s Cup Defence

Never been done before

Robbie got his start in one-designs like the Etchells but he also covered the other end of the size spectrum; Jim Kilroy ordered a set of sails for his latest Kialoa before the new Doyle loft was even fully built out. The first order for what was then called a Megayacht inventory came in 1985.

It was soon after that when Robbie made an important connection on a flight back from Bermuda. Though he can’t remember why he was even there, the event had gone well enough to reward himself with a first-class ticket home – and he found himself sitting next to Tom Perkins. Soon he was creating sails for the 45m Andromeda, which eventually led to an even more exciting challenge: powering Perkins’ unprecedented three-masted clipper ship, Maltese Falcon.

By then son Tyler was working towards that Stanford PhD so he could help steer Falcon’s owner toward a Dacron sailplan.

‘Tyler’s analysis was really important,’ Robbie says. ‘The leeches are longer than the centre seams, so having laminated sails would have been pretty difficult. Tyler’s work showed that with yardarms there was no huge load. My back of the enve- lope analysis had shown the same thing, but Tyler was able to prove it!’

‘If I could describe what motivates Robbie and Tyler alike,’ Janet says, ‘it’s the unknown. Any project that has never been done before, they get their teeth into…’

‘Or it’s the inability to say no,’ Robbie jokes, before nodding his agreement. ‘If it’s never been done before, that’s really what interests me.’

Later, Robbie says Maltese Falcon might have been his best project. ‘It was so different. And I knew it could work, because of the work Tyler had done.’

But he quickly lists off other favourites, including the roller boom for superyachts that led to his only commercial project: 4,000lb roll-up curtains for The Shed arts centre in New York City. He thinks that success might have led to other non- marine work if they hadn’t sold the busi- ness, though ‘it was no fun working with New York contractors’.

Sailing every moment

When I ask for his favourite sailing experi- ence the surprising answer takes us all the way back to the Finn. ‘I just love the whole rhythm of it. I love the simplicity of it. Liter- ally you roll your boat in the water and you go sailing. You’re sailing every moment. No crew meetings and all that sort of stuff.’

On bigger boats, of course, there’s no way around crew meetings. ‘You’ve got to get a team working together. But it just takes up so much time! In the Finn you just go sailing – and I knew everybody in the class.’

He has fond memories of cooking burgers around an open fire, chatting with competi- tors; a stark contrast to superyacht regattas where ‘you hardly ever meet the other people because you all go straight back to eat in your villas or hotels. I guess the younger guys get to see each other a little, at the same bars. But it’s not quite the same…’

Full circle

In 2017 Robbie sold the company to Doyle International (which more recently became part of the North Technology Group). The US headquarters moved down to Newport, but his employees asked him to keep the local loft open – and that’s where the One Design headquarters remain. ‘We actually run quite profitably now, because we have no overheads. This is the secret.’ And at an age when most people slow down Robbie returned to his roots. ‘I’m back designing sails again! Which I started doing in 1972. 50 years later… Of course sail design now requires new skills and I had to teach myself how to use all the 3D simulation stuff; but that’s better in semi- retirement than doing crossword puzzles because it challenges your mind.’

Robbie’s now got several fused verte- brae, so ‘it’s really hard to look up at a sail. It’s hard enough to look left and right. And I just don’t enjoy going out there and not being able to physically do well.’ (Also, sailing’s endless quest for perfection ‘still just drives me crazy’.) ‘So I’ve taken up golf, which I’m trying to get better at!’ Again Janet paints the bigger picture. ‘Robbie figured, why not take up a sport that you’ve got a chance to get better at, when every other sport at this age you’re getting worse at?’

There’s a new boat project too: the Storm 18, designed specifically for yacht club fleets. ‘It’s a fun little boat, and I’ve had a lot to do with the development of the rig… and everything else,’ Robbie says, adding how he’s looking forward to sailing the prototype the following weekend.

We linger over tea and dessert, trying to fit in just one more story… and as I regret- fully take my leave it now makes sense that this iconic sailor doesn’t bother to display any trophies. He’s still moving forwards, towards the unknown – a feat only made possible by both the skills and clear vision of his life partner.

‘Between us now we figure we have one brain,’ Janet laughs, as she presses some local chocolate into my hands for the long drive ahead. No such thing as Seahorse fringe benefits? I beg to differ.

* Left coast rival Robbie Haines. Mean- while, Eric Doyle works for North, lives in San Diego and is a Star World Champion… Eric Doyle is no relation to either brand or family (clear as mud – Ed)

ABOUT DOYLE SAILS // As sailors, our obsession with sailing connects us to the water. The water is our playground, a sanctuary where we seek enjoyment, a competitive playing field where we race; it’s sometimes our home and always a place that unlocks our sense of adventure wherever that adventure might take us.

Our obsession with sailing takes us to every corner of the world and onboard every yacht. We become part of teams, share in the adventures of friends and families, sharing our knowledge and experience with those who have the same passion for sailing as we do. Sailing is in our DNA, where the water unlocks our sense of adventure. We are the custodians of a legacy that has been supporting sailors for close to four decades, and while our world changes around us, our commitment to sailors who seek the same enjoyment and adventure as we do hasn’t.

From our sailors to yours, we are your experts in sailing. Your adventure starts with Doyle. By sailors, for sailors.

ABOUT SEAHORSE MAGAZINE // Take advantage of our very best subscription offer or order a single copy of this issue of Seahorse.

Online at: www.seahorse.co.uk/shop

Or via email: subscriptions@seahorse.co.uk

Great article – I remember Robbie from my 110 days, college and Finn racing. He was always a great competitor. Glad he put retirement behind him.